Fallacy of Expert Opinion

For most of recorded dating back to the days of Hippocrates, medical education has been heavily a top down transfer to knowledge. It is only in the "recent" past has there been a recognition that no one individual can have complete knowledge of human body as a whole or even to a degree an individual organ system.

A simple google search of the number of published articles over the past next 7 decades show the vast and expanding nature of what constitutes medical knowledge

| Year | Total Citations |

|---|---|

| 2020 | 986,012 |

| 2015 | 878,407 |

| 2010 | 735,005 |

| 2005 | 609,839 |

| 2000 | 485,493 |

| 1995 | 416,454 |

| 1990 | 388,120 |

| 1985 | 318,108 |

| 1980 | 272,538 |

| 1975 | 244,105 |

| 1970 | 211,330 |

| 1965 | 173,135 |

When approached from this perspective, the task of making a medical decision using the best available information is at best daunting if not seeming down right impossible.

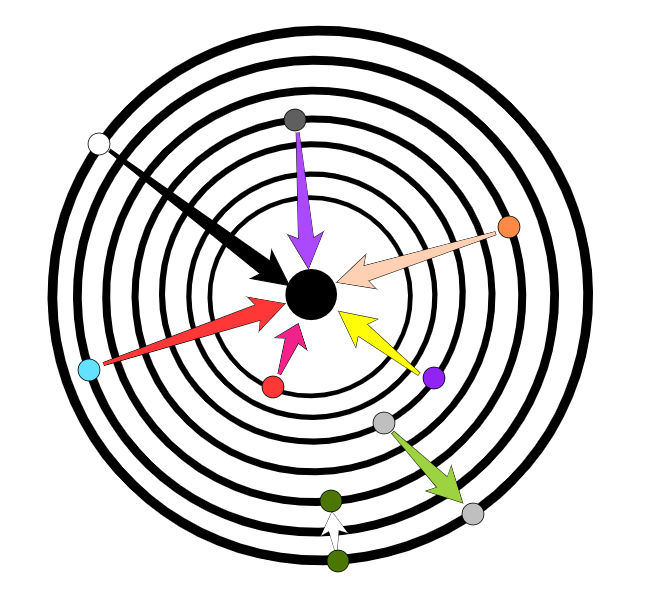

Early in my internship, we were sitting in a conference room meeting with an attending physician to discuss the "challenging case" of the week, when the attending, Dr Jain who happened to be a continental Indian, drew the figure below on the board.

Perhaps his perspective was from having grown up in India, but I remember and incorporate his words to this day.

As we gain experience from time and education we all move with time towards the inner circles of knowledge. For our overall knowledge the process is slow like the green circle at the bottom of the graph. Yet no one exist at the center or nirvana of all medical knowledge. For a given topic it is within the grasp of anyone, no matter their starting orbit, to touch nirvana for that given topic. The closer your orbit the faster the process. There was at a time in my memory when seeking nirvana meant using PubMed and hours in the library with the copy machine collecting articles. As we start to enter the age of AI assisted searches, the ability is at the fingertips of anyone. Since medical knowledge is ever changing, we need to be life long "students", or else we will find ourselves like the gray circle and our care becomes dated and our patients suffer.

The first way I have embraced this approach it with the interpretation of core pulmonary exams. When I get a referral for a patient with an abnormal CT or CXR I review the scan and any available comparison information. Comparison information can come from unexpected sources, such at the lung cuts of abdominal CT scans. After I have reviewed the data I formulate my personal interpretation, then at this point I review the report for the study. Even if there is good concordance between the two, we need to incorporate what we learn from the patient and make adjustments in our recommendations and conclusions.

When I come to a conclusion that differs from the report, I want to be prepared to explain to a patient and family why I am recommending a treatment or evaluation course that differs from the expert.

At this stage I do need to emphasize that I am not insinuating that everyone is stupid except me, but just because someone has a degree or a board certification that they are competent or having included all the relevant information into a conclusion.

The second area strongly relates to my last statement. Just because you may be early in your journey, it does not mean that for a given topic your level of knowledge may not equal or exceed a so-called expert. My career has been primarily at regional referral centers. One day a family was requesting a transfer to a University facility, not because the patient needed a higher level of care but a perception that this institution was "better" . The hospitalist on the case made a comment in response to the request: "They are not gods!". Just because you choose to practice in a small town or rural setting does not mean that by the nature of that decision that you must be incompetent. Likewise being at an tertiary care center is not a guarantee one is getting cutting edge care. We all in our way need to strive for nirvana!